I’ve been watching our driver closely since I noticed our taxi drifting in and out of our lane.

I can see his eyelids hanging heavy, fighting to stay open. His eyes are watery. He blinks short and often. Then, one blink is too slow. He starts to nod off. I quickly throw my right hand across the divide of our seats and shake his shoulder. His eyes spring open and he instinctively sits taller, looking straight ahead at the road as if nothing has happened.

“Are you okay?” I ask.

“Ye-,” he mutters through his thick accent.

Less than a minute passes. His head nods down again.

I jab him a bit stronger now and repeat myself, “…Okay?”

“Yes,” he replies.

We’re going to die in this car, I hear myself say, in the Middle-of-Nowhere, India.

It’s nearly 5:30 AM. We’ve been driving for two hours and still have four hours to go. Liza and Caroline are asleep in the backseat. We are somewhere between New Delhi and Rishikesh, India, on our way to meet another dozen Westerners for a 10-day yoga retreat and immersion experience in the yoga capital of the world.

That is, if our driver can stay awake long enough to get us there.

Liza, Caroline and I at Boston Logan airport en route to India.

Our relationship got off to a rocky start.

It began around 2:30 AM outside of the New Delhi airport when Liza, Caroline and I emerged from the arrivals terminal. We made it a few steps outside of the automatic doors before halting to a standstill. Some 30 feet from where armed security guards were posted swarmed a sea of dark-eyed cabbies and bus drivers, most mustached, most in white button down shirts, hanging over a thick iron railing.

It was eerily quiet for how crowded it was.

The exterior of the airport was cavernous and intimidating. Enormous stone columns fit for a royal palace staggered beyond the airport’s pickup alleyway, propping up the huge over-hanging level of concourse above.

A humid, hazy cloud of smog crept in from beyond the orange glow of the airport’s street lights, casting a veil between us and the dark of night in New Delhi.

Our eyes scoured over the crowd of drivers and cabbies. “That’s us,” I told the man who held the sign with our names on it. It was he who would become our driver for all these hours later. At last, finally, we felt like we could breathe a sigh of relief. After nearly 30 hours of travel from Boston through Amsterdam to New Delhi, this long excursion to India seemed to be turning a corner.

But the feeling of relief from finally having arrived in India began to turn instead to confusion and frustration.

The man who held the sign with our names of it spoke better English than I spoke Hindi, yet Liza, Caroline and I couldn’t understand why we weren’t leaving the airport just yet.

“You pay?” he asked, over and over again. This ride to Rishikesh was already paid for in advance and organized by a local guide named Sahdev.

Five minutes of choppy translation later and our discussion with the man holding the sign had become a group dialogue with nearly ten people. The longer our chat with our driver went, other drivers began to huddle around. Presumably they had known our driver. A group of five or six of them interjected to speak Hindi with one another as each of our respective groups, we travelers and they local drivers, tried to decipher what the other group was trying to communicate.

Liza, Caroline and I infer that our driver wants us to wait for another group of fellow retreat-goers, who were arriving within an hour, before heading to Rishikesh together.

“Fifteen minute,” he told us.

“That’s fine,” we said. We’ve made it this far. What’s another fifteen minutes?

“You wait,” he said, after moving us beyond the crowd and near a coffee stand before he disappeared back into the crowd of men.

Forty minutes passed.

There we stood, being eyed curiously by passers-by and approached a dozen times by other drivers hoping to make a payday.

Completely exhausted and starting to feel like we were having one pulled over on us, I felt the no-nonsense, get-shit-done demeanor of my father wake up in me. Patience is one thing, but waiting on someone else to make a decision for you is a sucker’s game. After 30 hours of being at the mercy of airlines, meal service, train schedules, security guards and now suspicious eyes, I felt my fuse finally burn down to nothing.

I’m over this. I’m finished with waiting. We need to hit the road.

“Alright, I’m done now,” I heard myself blurt out to Liza and Caroline. “Wait here,” I told the girls, and headed back into the sea of cabbies to try to find our guy.

English and Hindi complement each other on signage at the New Delhi airport; outside, they clashed.

Half a world away. 3:20 AM. And being told, “You wait,” by some guy I didn’t know and didn’t trust?

Hell no.

It’s in moments like these when the poet in me, the yogi and the renaissance man, goes on hiatus. I hear a voice of reason in the back of my head, telling me, Just wait a bit longer, just be patient, remember compassion and empathy and everything you strive to live by.

But the animal in me, tired and feeling threatened, knows that survival, not politeness or idealism, takes precedent here.

I pulled my phone out of my pocket and started to dial Sahdev, our guide who I had still never spoken to. He was my wildcard for getting us out of there. As the phone rang for Sahdev, I sieved through the dense crowd of drivers and tried to recognize just one face of the mustached bunch in white shirts. I would never have found him if I hadn’t thought to look for someone holding a sign for those companions of ours who were due to arrive within the hour.

“Hello?” Sahdev answered his phone, perhaps startled out of his sleep.

“Sahdev, this is Dave Ursillo,” I started bluntly, like some hotshot politician might talk to someone who he knows knows him. Sahdev had no idea of who I was. And I knew that. It was tactical.

“I’m with the yoga group, we’re being told to wait here and that’s just not going to work. I need you to tell these guys that we’re leaving now.”

One thing I’ve held onto since leaving the world of politics is a special tactic for getting things done while communicating on the phone: speaking so certainly to someone–as if he knows who you are–that he starts to doubt his own memory, and perhaps, just perhaps, starts to presume that he actually does know who you are. Or, that he damn well ought to.

Besides, a man who truly knows himself makes his introduction with his full name.

I told our driver that we were to leave immediately–no more waiting. Our driver and his group of companions huddled around to listen, and a group of cabbies and bus drivers all found the dialogue quite entertaining. Suddenly, the lone white guy in a sea full of Indian men who didn’t want to stand out was now standing front and center before the crowd.

“Ten minute,” the driver told me.

“Sahdev,” I said into my phone, “Tell him we’re leaving now.” I handed my phone to our driver and after a few minutes of exchange, the driver handed back my phone. With a look of frustration, he said something to his companions before he looked at me.

“Okay. We go,” he said.

Finally.

We followed our driver to his car in the parking garage. He wasn’t interested in helping, let alone saying anything to us. We loaded our bags into his cab. One of us would be sitting up front with him in the passenger’s seat.

“I guess that should be me, shouldn’t it?” I told the girls.

This is going to be an awkward, interesting ride, I thought to myself.

And so we exited layer upon layer of security encircling the airport. Checkpoints and guards. Walls and fences. Before long, we passed into the empty, haze-covered streets of New Delhi to get our first glimpses of India in the dead of night. The drive began quietly, without any words spoken. Liza, Caroline and I were exhausted, and knew that we had a long drive ahead of us.

Two hours have since passed.

Now, I’m tasked to keep our driver awake long enough so that this 30-hour excursion from the United States to India doesn’t end in a crumpled heap on the side of the road.

Roadside restaurant/cafe installments were scattered across highways, serving locals with snacks, tea, naan and more.

I can understand why he’s so exhausted.

New Delhi had stretched on forever and ever, in repeating miles of concrete bridges and vacant pavement that never seemed to end. It took us two hours to escape the never-ending city, and those two hours were wild, hectic, nerve-wracking, and emotionally taxing.

Even in the dead of night, India is bustling.

We weaved in and out of traffic between overloaded trucks and passenger buses so full that they looked ready to tip over. We’ve dodged head-on collisions from speeding cars, avoided stray dogs and a few cows, passed bicycles and tractors and jaywalking pedestrians. We zoomed by families with young children who were walking down unlit highways at 4:30 AM.

I sat there wondering, Why are all of these people out here so late? Where are they going? What are they doing?

The answer was probably that they just have to be getting to wherever they’re going. That they don’t have the means to hop in a car and get there in a few minutes, and instead need to walk for hours.

The roads began to open up as we left New Delhi’s center. Repeating concrete bridge installments and roadways cleared into long stretches of one-lane highways with small homes, nondescript buildings and storefronts edging the roadway uncomfortably close.

A spat of red and green fireworks suddenly popped off in the distance to our right; it looked as if a festival was still waxing on through the early morning hours. It is, after all, the end of the Dewali festival here. Revelers crossed the street in front of our speeding car, running through traffic without a hesitation or care.

Every now and again, the thick, cloudy air would turn sour like sulfur; utterly putrid and polluted. I tried to brave the stench at first, but it was too overwhelming. I pulled the collar of my shirt up over my nose and mouth to shield a bit of the odor. Our driver, next to me, coughed and wheezed his way through it. A thicker and thicker cloud of smog then began to sink in, making the road itself barely visible.

After two hours of riding shotgun with him, I finally understand why he might have wanted to delay this long journey for even another “fifteen minutes.”

It’s been hellishly intense.

Even if he’s used to this kind of driving, nothing could possibly make it any less mentally taxing.

I think to myself that our driver has probably been awake all night, too. Maybe longer. And whatever energy that he had left he’s surely spent on the wild drive out of New Delhi and through this lively, chaotic night.

It has taken me all of these two-plus hours of driving through India with him for my brow to finally unfurrow; for the no-nonsense demeanor that I was counting on to get our journey moving to slowly whither and wash away.

The animal is gone, the poet is back.

I forced his hand to get this long drive started, and the least I can do is sit here with him and not in spite of him. I feel compelled to stay awake too, since he has to. And there are few things I would give up to see these hours’ worth of scene after scene, little speeding glimpses, of thousands of lives a half of the world away from mine, maneuvering in the dark of night as if it was day.

The simple makings of a roadside cafe on Highway 58, India.

After he falls asleep at the wheel a third time, I try to tell him to stop for coffee or tea.

But he seems to not want to stop for himself.

We drive past a few street side installments of outdoor shops, almost like open air convenience stores, set up with colorful plastic chairs and tables and the exact same Pepsi ads hanging all around the exterior. They’re lit with a dozen fluorescent light bulbs, hanging vertically from tree limbs overhead.

“You want?” he asks me.

“No,” I tell him, “I’m fine. For you.”

He doesn’t acknowledge, and just keeps driving. It’s clear that language barrier is confusing him. I figure he is thinking that he does not want to stop the very journey that I forced him to start with haste. I wonder if he’ll stop, then, if I tell him that I want coffee or tea.

He agrees.

A mile or two later, he pulls over at one of these indoor-outdoor Pepsi installments and parks. The girls are still asleep in the back seat.

“One coffee?” He asks me. I knew that he wouldn’t stop to get himself one if I didn’t tell him to.

“Two,” I tell him, “One for me and one for you, okay?”

“Yes,” he says, “You come.”

He exits the cab and the girls wake up at the sound of his drivers’ side door shutting.

“We’re stopping for coffee,” I tell them, “I have no idea how this is going to go.”

The driver waited for me and I met him behind our cab, parked on the side of the highway between two enormous trucks. It’s only fitting that here we become the very jay-walking prey that we’ve been dodging on our drive for the past two hours. In unison we peek around the parked bus to our right, looking for any headlights to pierce through the dense smog. A few whiz by. Seeing our break, we scamper across the highway together, hopping over a high-curbed median covered with dirt and garbage, and dart across the opposite lane of traffic to reach the rest stop.

“You okay?” I jest with him, just happy that we’re making progress to Rishikesh and that he’s fully awake. I add a pat to his shoulder.

“Yes,” he smiles, looking like he wants to say more but lacks the words to say it.

“Long night,” I try to finish for him.

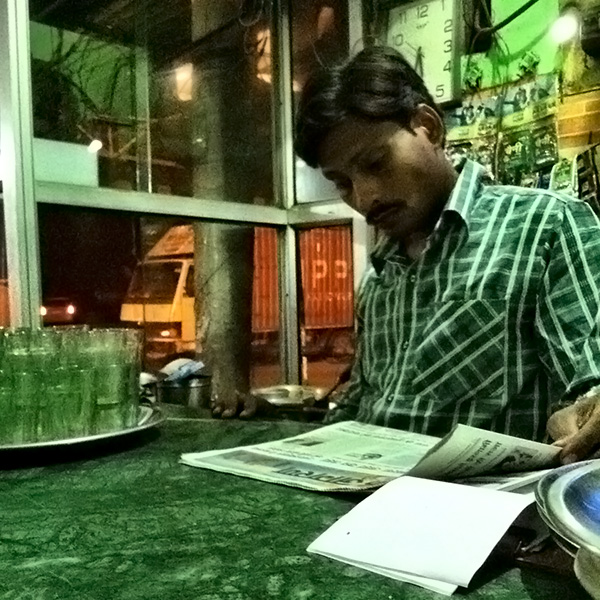

We enter the rest stop. One young man is behind the counter half-asleep, reading a newspaper with one hand while brewing a pot of masala chai tea with his other. Behind him sits an older gentleman, facing away from us at the counter, looking into a nook of deities and statuettes. He is in prayer, burning incense. Behind us in a reflective window separates customers from another man who is grilling fresh naan.

Our driver speaks in Hindi to the uninterested man who is reading his newspaper.

“No coffee,” the driver tells me.

“Tea, then,” I say.

A few minutes pass and the uninterested man pours us two masala chai teas into petite drinking glasses. I offer to buy.

“Twenty rupee,” the driver says.

I hand a 100 rupee bill over to the uninterested man, who gives me my change without looking up.

The driver and I take a couple steps onto the patio by the plastic chairs and tables and begin to drink.

I start to feel more and more eyes of young Indian men, who’ve stopped for tea or naan, snacks or water, upon me.

They aren’t just hovering curiously. They stop and blankly stare.

I’m so exhausted that nothing else matters but the hot glass in my hand; the sweet, spiced tea with heavy milk that warms my throat and all at once makes me feel comforted, safe, and at home–even here, in the Middle-of-Nowhere, India, standing in shack with a middle-aged, mustached cab driver at 5:38 AM on a Thursday morning.

A stray dog wanders over and sits outside the store, looking for a scrap. A man in a scarf pumps water from a well into a glass milk bottle. A parked truck is stacked with hundreds of chicken cages, full to the brim with the birds. Behind me, I hear the grilling of dough.

I feel my soul starting to settle in. I feel like I’m here now–my soul has caught up to my body.

This is my roadside glimpse to the pace and flow of life in this corner of India, the sun not yet risen, and nothing much to look at besides a few faces and over-packed buses parked in a row.

This is the journey, I remember.

Taking my tea in my right hand, I cheers the driver’s own glass to thank without words what he has already done for us tonight. I know it hasn’t been easy. I know I haven’t been easy. And there are still hours left to go.

I finish my chai tea still standing there, and look around for what to do with the glass. I peek back towards the uninterested man at the counter, and place my glass in a bin on the steel counter with other glasses that appear dirty.

Seeing this, the driver picks up the glass I just put down, looks at me with a smile, and places it instead on the bar table in front of us where other dirty glasses had been placed.

I read his smiling eyes and understand my folly. The glasses in that tray were clean. (At least, in theory.)

I think to say Thank you, but just smile instead.

The words aren’t needed anymore.

As the sun came up, smog clouded the sight of cars on the road.

It was another hour of driving before daylight came.

The smog was thick and intense, blinding our drive to a crawl for miles.

But the worry has left me. Now I have a front seat view to a whole new country waking up, and what scenes we see. The sun fights to break beyond the polluted haze, illuminating men and animals in fields, towering trees and even more sprawling streets and little towns full of new faces, storefronts and broken houses.

With the daylight comes a new feeling of chance, of hope.

And, thankfully, the promise that this long journey is finally drawing to a close.

This is India. We’re here. We made it.

Having stood watch for over five hours with him, I feel a silent bond with our driver, who has gone to unthinkable lengths to get us even further away from home and deep into his homeland.

All of a sudden, I feel my eyelids hang heavy. They fight to stay open. My eyes are watery. I blink short and often.

But one blink is too slow. I start to nod off.

I wake up to the feeling of our cab stopping at the side of the road.

I jerk my head up, sitting taller, startled and pretending like nothing happened.

I look to our driver, who’s sitting there and smiling at me.

“Tea?” he asks.

I look forward to see that we’ve stopped at another outdoor rest stop and cafe, with Pepsi signs galore, and decked out like the rest with plastic chairs and tables all around.

“Yes,” I tell him, “I would love some tea.”

“This time,” he says, “I buy.”

The man, the myth, the legend himself. Our driver, my chai tea buddy.

It’s been three weeks since I got home from India.

I’m still processing a lot of what I saw, felt and experienced. This story is one snapshot into what my small, small window of India was for me.

I hope in the coming weeks to share some more essays, thoughts and stories–with plenty of photos from throughout the excursion–to bring you into a look of what life was like, through my eyes, in India.

In the meantime, I’m holding my masala chai high to you. Cheers!

P.S. — Read the sequel to this piece here: Why I Went Back to India