The primary contributing factor in the earliest stages of European Integration — and that would eventually lead to the creation of the modern European Union — was a universal interest in national security.

And yet, national security issues are exactly what prevents European Integration from progressing as far as it was once desired.

The European states began to unite in the 1950’s after two devastating world wars that demanded a forum for diplomacy that might allow the continent to avoid an unsurvivable third.

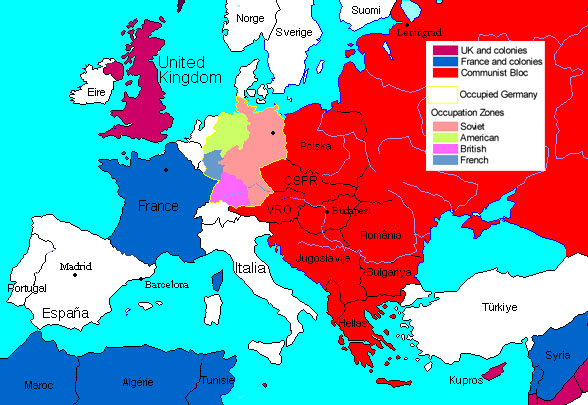

Meanwhile, national security pressed heavily upon the minds of Europeans as they faced possible consumption by the ever-expanding Soviet monster to the East. While security was the primary factor of early European Integration, states’ perpetual refusal to compromise their sovereign right to common defense and foreign policy remains the major hurtle that hinders European Integration from progressing further.

This paper analyzes several junctures of European Integration through the lens of the Realism theory in the study of International Relations, and on two distinct levels that effectively explain early European Integration:

- First, the Realist perspective regarding the interaction between individual states (i.e. France’s proposal of the EDC to stall German militaristic buildup), and,

- Second, the Realist perspective regarding the interaction between an integrated Europe as an entity and other superpowers (i.e. the early EEC attempting to balance power with the USSR & United States).

Understanding the theory of “Realism”

In the study of International Relations, Realism is a theory that focuses on states’ interests in security. Realists interpret interaction between nations uniquely. States are the dominant actors in a global system of anarchy: they interact with each other but nations have no body of power or international organization that truly controls them. States are individual and rational — they act in their own self-interest because the international system is in a constant state of anarchy.

Realists have a very condescending view of international cooperation and intergovernmental institutions, which they believe are highly idealistic.

Realists understand international cooperation through institutions as an attempt by states to diplomatically approach international dilemmas.

While institutions and international cooperation might theoretically help solve such a dilemma,Realists believe that institutions don’t change the nature of self-interest of states acting in international relations, and that a state never willfully gives up its sovereign right to security — its control on law, order, and power within its own borders. The only reason why a state may give up some power to the institution is that it hopes that the institution might bring about a resolution to an international dilemma more successfully or decisively than if the state acted alone.

The traditional Realist understanding of the first step of integrating Europe is that mid-level powers (France and Germany) were trying to balance power with the United States and the Soviet Union. That is the perspective of security on a global scale; but also within Europe are the individual self interests of the states involved.

The Status of Europe after Two World Wars

The earliest attempt of modern European Integration occurred in the 1950s after two German-led World Wars. “The German Problem,” as it was dubbed, posed a national security dilemma for France, the United States, Britain, and even Germany itself. Each state held significant interest in either rebuilding — or hampering the rebuilding — of Germany after two world wars because they feared Germany may go on to cause a third.

The United States found itself in a developing conflict of interests with the Soviet Union in the 1940s; the precursor to the Cold War. At the time, the United States was exercising the foreign policy dubbed by George F. Kennan as a “policy of containment,” one that would not militaristically engage the Soviet Union but aid and strengthen American interests so as to contain Communism from spreading.

It was in the interest of the U.S. to see West Germany not fall under the Soviet sphere of influence. East Germany was already occupied by the Red Army, and the U.S. feared that the rest of Europe might fall to the USSR if Communism took hold in West Germany.

West Germany served as a border protecting Western Europe from Communism, and the United States sought to rebuild German power through remilitarization as soon as possible. With Communism in the 1950’s understood to be a major threat to the security of the United States (as it would be throughout the Cold War), America’s national security interests played a large roll in pushing for European Integration.

After World War II, Germany was almost wholly dependent upon its former enemies for aid. Germany was occupied by the former Allies and sought to “re-militarize” and regain complete sovereignty as soon as possible. France, though, was in fear of another German-led war. Four wars occurred between France and Germany in only seventy years:

- The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871)

- World War I (1914-1918)

- The Ruhr Invasion (1923-1924)

- World War II (1939-1945)

With Germany as the aggressor in every incident, France had good reason to distrust German power and believe that it was possible for another military conflict to evolve in the future. France had learned from its national security mistakes in the past and wanted Germany to remain weak and without a military, at least in the interim while France itself tried to regain economic and military power.

In 1950, French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman outlined a plan in “The Schuman Declaration” through which, he theorized, Germany would become economically interdependent with its European neighbors and be physically unable to wage war in Europe without a financial implosion.

The plan outlined a coalition between Germany and France in the production of coal and steel, the two primary war-making materials of the time. The goal of the Declaration was to “build a peaceful, united Europe one step at a time,”[2] through integrating Germany and binding it with the rest of Europe. The Schuman Declaration was related to the security of the continent as a whole, and to the self-interested security of France, knowing that it would be virtually impossible for an integrated-Germany to cause another war.

What resulted from the Schuman Declaration was the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1952. The ECSC was the first step of European Integration in the 20th century after the continent’s bloody past. The ECSC was called an unofficial Franco-German peace treaty and a form of reconciliation for the former enemies. The step towards integration, though, was directly related to the security of the continent and had much less to do with grandiose dreams of a “supra-nationalist” European state.

The ECSC and the EDC: the First Steps toward European Integration

The foundation of the ECSC was grounded on desires for a lasting security in Europe and that might ensure peaceful relations between for former enemies.

But there were a series of security issues that would arise in the 1950s that would lead Europe to push for integrated security initiatives.

First, the Korean War began in 1950 when the Communist North Korea invaded its lower democratic half, South Korea. The war between the split Korea had eerily similar pretenses to East Germany and West Germany: one communist half, one democratic half, and no precursor that war was on the horizon.

Because the Korean War began so abruptly, anxious Europeans felt pressure to begin a push to create a common defense initiative, the European Defense Community (EDC). In 1950, Konrad Adenauer, West Germany’s first chancellor, voiced his favor for the proposed European Defense Community that was introduced by the French in the Pleven Plan.

The Pleven Plan boldly called for a united European Army. Adenauer believed the Plan would help bolster the defense of West Germany from its communist neighbor, East Germany. The United States understood that a Soviet invasion of Western Germany was palpable and liked seeing Europe take initiative regarding their security (which ultimately played into the safety of the United States itself).

The Realist Perspective on Early European Integration

A Realist might argue that the reason that the EDC initiative came about was because security, as the issue of utmost importance, took center stage in world events and Europeans responded by looking to create a single, unified and powerful armed forces. But, in fact, European security was not truly the driving factor behind this apparent push for European Integration. France knew that it was unrealistic that the Pleven Plan would actually be accepted by other European member-states.

In historical hindsight, the initiative was actually a deceptive strategy by France who actually sought to stall for time in order to build up their own French armed forces while slowing German remilitarization, which they strongly opposed. Their intentions became clear in 1954, when France officially voted against their own initiative, the Pleven Plan.

France attempted to stall Germany’s remilitarization long enough to build up the French military, but U.S. pressure ultimately ended the debates and the result did not completely produce France’s wishes. The next juncture in the course of European Integration that would be specifically determined by self-interested states (directly tied to security) would be three years later in 1957: the signing of Treaty of Rome.

European Integration Accelerates throughout the 1950’s.

The Treaty of Rome was a framework document that established the European Economic Community (EEC) and was signed by France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg in 1957.

In what became known as the Treaty of Rome, an instance of “incomplete contracting,” states sought to establish a European customs union and develop framework for future institutions, such as the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). In the days of discussions leading to the Treaty of Rome, verbal and political battles between France, Germany and Britain would all help reveal that ensuring the security of each respective state was the chief objective.

German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer sought to establish German power and sovereignty in the 1950s. The foreign policy approach of Germany under Adenauer was “Westbindung” or West-oriented integration, as opposed to the approach of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) who sought Eastern-integration towards the Soviet Union. Westbindung was Adenauer’s attempt at binding the German state to the West, namely France, through institutions.

The other main state taking part in the negotiations of the Treaty of Rome was France under Charles de Gaulle.

De Gaulle was a nationalist with a particular disdain for Germany, Britain and the United States. De Gaulle sought to make secure the French state and economy while in office. De Gaulle’s foreign policy approach is explained by his belief that the world would become multipolar again in the near future, with the main states being the United States, the USSR, China, and a united Europe.

De Gaulle’s belief led him to push for European Integration that would make Europe a dominant force in negotiations with other world superpowers; yet at the same time De Gaulle’s nationalist spirit prevented any major integration from occurring. In the negotiations of the Treaty of Rome, France demanded preferential treatment for former French colonies, while outlining strict guidelines for the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

France, with a whopping 25% of its workforce in agriculture, sought to secure the CAP in its favor because of the vast amounts of capital the nation would receive from the EEC.

Adenauer, after disputing with de Gaulle over the extreme demands made by the French, agreed to the CAP guidelines and French preferential treatment for former colonies, that in no way benefited Germany. This begs the question, why did Adenauer give in to France’s nationalist demands that hindered European Integration?

Germany Capitulates to French Demands

Theorists have argued that the reason that Adenauer caved in to French demands in the Treaty of Rome and a “small Europe” rather than a free-trade-driven “big Europe” was because Adenauer wanted Germany to be tied up with the French through institutions and integration.

Theorists continue to argue that Adenauer felt that geopolitical ties between France and Germany could restrain the two states from engaging in future warfare. Adenauer was distrustful that democracy could hold in Germany.

Adenauer sought to protect Germany from itself by binding the state to other states through international institutions. By joining and integrating Germany with Europe, Adenauer felt that Germany’s militaristic tendencies could be barred from flaring up again.

Adenauer sought to protect Germany from itself by binding the state to other states through international institutions. By joining and integrating Germany with Europe, Adenauer felt that Germany’s militaristic tendencies could be barred from flaring up again.

The Realist theory suggests a more self-interested plot on behalf of Adenauer: Realists argue that “the German legacy” as an aggressor with a dishonorable and bloody past was restraining Germany from being able to make any strong demands in its favor.

Realists argue that Germany sought to maximize its strength and power through a backdoor of a united and integrated Europe, in order to regain power and achieve complete sovereignty. Germany’s goal of attempting to gain strength and power through European Integration proves to Realists that security was Adenauer’s principal interest, and that the main drive for European Integration has been security. Furthermore, the concessions given to France in the Treaty of Rome, while strictly economic, negatively set the stage for later European negotiations.

Future negotiations would reflect the set precedent of caving to a state’s nationalist demands (as Adenauer did with de Gaulle) in the name of a state’s self-interest.

This failure of the Treaty of Rome was critical to the future of European Integration, by making nationalist concessions and supranational shortcomings the norm of integration. Security and foreign policy issues would be impacted the most in future attempts of European Integration, and may be an adequate explanation for why current European Integration seems to have hit a roadblock in progression.

Britain Acts as a Realist and Attempts to Kill the EEC with the EFTA

After the EEC was created through the Treaty of Rome, Britain sought to destroy the EEC through a rival integration organization, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

The British motto when referring to the EEC was “Kill it or let it collapse;” Britain believed that it would inevitably collapse on its own, or that Britain should accelerate its downfall. In doing so, Britain displayed their significant Realist interest in expanding their financial power by way of destroying the EEC out of fear that a recent enemy (Germany) and a traditional rival (France) would become more powerful than Britain.

With Germany’s bloody legacy still fresh in British minds, Britain, like France, feared German power and remilitarization.

While Britain feared German power, it also sought to protect its sovereignty and status as a great power, while refraining from relinquishing any sovereignty to a supranational organization like the EEC. The British were also interested in maintaining the “special relationship” between the U.K. and the United States. Their ties to the United States and their wishes to keep their superpower-ally close show that security interests were of utmost importance for Britain.

American President John F. Kennedy opposed the British creation of a rival organization to the EEC. The United States was interested in seeing a united Europe gain strength against the threat of the USSR. Two rival organizations showed the United States and the USSR that a divided Europe could possibly be exploited in its failure to unite.

Caving to U.S. pressure, Britain finally applied for membership of the EEC. The final decision of whether Britain would be allowed to enter the EEC, an organization they attempted to destroy, would rest upon Charles de Gaulle.

- First, the nationalist de Gaulle did not want France to lose its position of power and prestige in the EEC, which would be inevitable if another strong player like Britain was allowed to join.

- Second, de Gaulle was concerned that the British would water-down CAP money (because of the small yet existing agricultural sector in Britain) that would ultimately undermine French capital and power.

- Third, de Gaulle saw the British entrance to the EEC as United States Trojan-horse into the European organization. De Gaulle saw this as very problematic if the United States could possibly interfere in the future multilateral world (that he believed was on the horizon), bargaining amongst the European states, and ultimately he though the United States would interfere with European security.

Soon thereafter, de Gaulle took great pleasure in vetoing the British application to EEC. The bargaining of the Treaty of Rome and the results from its signing portray to Realists that security was the driving factor and objective behind every state involved, and even those who were not (like the United States).

Conclusions on the Realist Perspective on European Integration

Realists find it difficult to explain European Integration because the very premise of integration is relinquishing some amount of power and giving it to an institution. While the theory of Realism fails to explain why EU member-states would ever relinquish some amount of power and sovereignty to an institution, it adequately explains its foundation and early behavior in the 1940s and 1950s and may actually exhibit why current attempts at further integration fail.

The early history of the European Union is not one of cooperative integration on behalf of the betterment of their citizens. Rather, origins of the EU is riddled with deception, hard-bargaining and even some chaos that was caused by European states’ being primarily self-interested in their national security.

While security was the causal factor of early European Union, it has also hindered further attempts at European Integration.

Numerous attempts to develop a common defense and foreign policy have failed because states refuse to relinquish their individual, sovereign rights that allow them to determine their own security policies. The Realist theory has proven why and how European Integration has come as far as it has, while also explaining why European Integration will not progress further on issues as important as national security.

Plagiarism warning: This essay is indexed in Google and internet-wide search engines, and will show in common plagiarism searches done by professors, teachers and in automated computerized tools that search the internet for plagiarism. Students, adequately cite your sources and do not plagiarize.